Parents outgunned in child welfare cases

Programs in Detroit, Flint show possibility for success

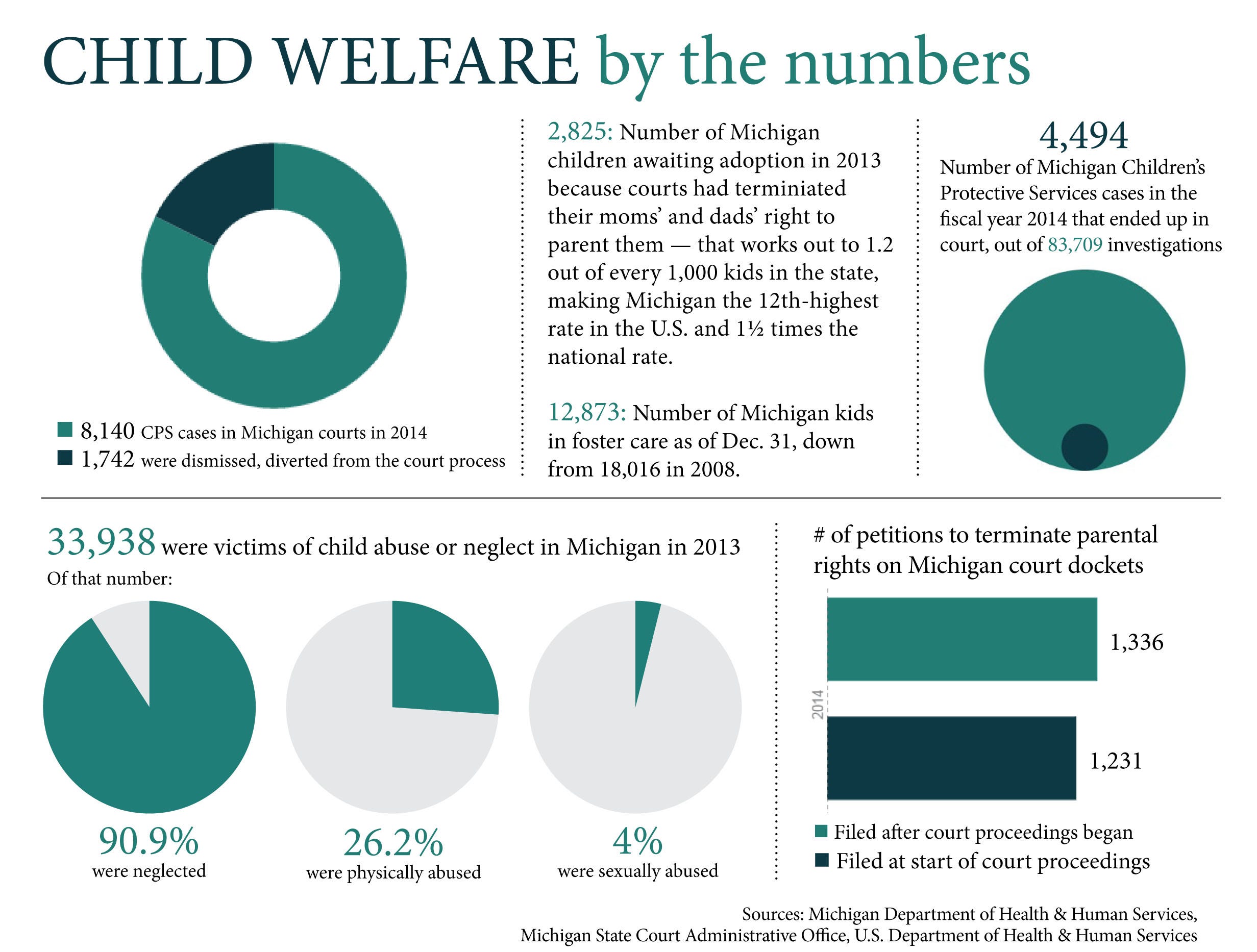

- Michigan has 12th highest rate of kids facing adoption because courts terminated parents' rights to them

- Parents must rely on their accuser for services to help get their kids back

- Child abuse and neglect cases happen in civil, not criminal court; burden of proof is much lower

LANSING – When he was 15, Lamar McGaughy lost his mother to drugs. He lost his siblings to Michigan’s foster care system.

Split up after their mother's death, McGaughy and his siblings barely know each other today.

The 38-year-old Detroit barber was afraid the same would happen to his son and daughter after their mother got into trouble with Michigan’s Children’s Protective Services. The court wouldn’t place his kids with him because he lacked legal custody over them, though he’d always been a part of their lives.

He had reason to be afraid. For most parents fighting CPS in court, "the system is really designed for them to lose,” said Liisa Speaker, a Lansing attorney who represents parents at the Michigan Court of Appeals. Michigan is caring for the nation's 12th-highest rate of kids awaiting adoption because judges terminated their parents' rights to them.

McGaughy got no help from the state agency legally required to do all it can to keep families together, because the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services doesn’t deal with custody paperwork. He got no help from the publicly funded defense that state law guarantees him. His court-appointed lawyer showed up the first day of his case and never showed up again.

Parent advocates say Michigan erects a wall between kids and their families because DHHS is the only agency helping parents overcome their struggles and at the same time is their courtroom opponent, logging those struggles as possible evidence against them. In child welfare cases, judges can issue lifelong penalties based on far less evidence than is required in criminal court. Most parents’ only defense is an overworked, underpaid court-appointed attorney.

Yet there are signs of a better way.

McGaughy’s family was saved by the Detroit Center for Family Advocacy, a small agency that prevents foster care in nearly 90% of its cases by offering parents targeted legal help and social work that costs a fraction of what taxpayers spend on foster care.

CPS manager: 'There's always a nuance to the cases'

DHHS officials welcome such work, but said the state already keeps most families together. Only about 5% of the nearly 84,000 cases CPS investigated in fiscal 2014 ended up in court. Petitions to permanently terminate parental rights were filed in only a fraction of those cases.

“Our job is not to go after parents and hold them accountable and make them pay for what they did,” said Colin Parks, the state’s CPS manager and a former investigator. “Our job is to keep children safe.”

‘A frightening amount of power’

Parents can lose their kids forever based on far less than the proof “beyond a reasonable doubt” it takes to send someone to prison. Parents often lose their kids without criminal charges. CPS cases happen in civil court.

Take the case of Cary Flagg, a Mecosta County father who lost his four girls over allegations of sexual abuse. He was never charged with a crime.

“I viewed it as a death sentence,” he said of losing his daughters.

(View a larger version of this image here.)

Flagg says prosecutors didn't have the proof needed to file charges. The Mecosta County prosecutor’s office refused to comment.

Proving a criminal case can take time, said John Murray, the chief Ingham County prosecutor in charge of CPS cases, and kids shouldn't be stuck with their abusers while the state gathers evidence.

Dad who lost parental rights: 'I'm trying to be hopeful'

Judges initially give CPS permission to remove kids from their homes if the agency has “probable cause,” the same amount of evidence a police officer needs to search someone’s car during a traffic stop.

After that is a hearing to determine if the state has proven the family's problems meet the standards for the court to take control over the children and order DHHS to provide services to the family. At this hearing, the state must prove its case by a “preponderance of the evidence,” meaning most of the evidence suggests the allegations against parents are true.

That hearing is the only time parents are entitled to a jury. Most parents waive that right and plead guilty, often advised by their attorneys to do so because court jurisdiction makes them eligible for services.

But the fight is often over then, because “once the court has jurisdiction, it has a frightening amount of power over these families,” said Tracy Green, DCFA legal director and a former DHHS foster care worker.

DATABASE: Michigan child welfare by county

The majority of petitions to terminate parental rights — granted by judges alone if the prosecution gives them “a firm belief or conviction” that the allegations are true — are filed because parents fail to comply or benefit from the services DHHS provides. It’s like getting probation after a trial and then having a judge sentence you to death for a probation violation, Green said.

And parents are asked to quickly turnaround their problems, even generational issues.

'No parent is given a shred of hope'

“I think it’s most egregious in cases that involve substance abuse,” said Shannon Urbon, managing director of the DCFA. “You’re expecting someone with a substance abuse problem to be able to get clean, stay clean, find housing and employment in 15 months or less, and also relapse and get back on track within 15 months. That’s impossible. Substance abuse is a lifelong challenge.”

Green said the real problem is that DHHS and the courts are too afraid of litigation. Since 2008, a federal court has monitored DHHS in a lawsuit filed over the deaths of three foster children.

“Nobody wants to have their name on the front page of the paper,” Green said, “which is really an unconstitutional approach to these cases.”

‘Makes lawyers nervous’

CPS has its horror stories. In Ingham County in 2010, for example, was the man who became legal guardian of a 14-year-old girl and impregnated her when she was 15.

Parents tell horror stories, too: Antonia Hernandez’ six kids, for example, were put in foster care for three weeks last year because CPS determined their campground in Otsego County was unsafe. Thing is, the family had a home in Ecorse and could’ve just returned there on day one. Nobody gave them the chance.

About 30% of CPS cases involve physical or sexual abuse. The remainder only allege neglect, such as dirty houses, improper supervision or failure to properly care for kids’ physical or emotional well-being. Poverty, mental health, substance abuse and domestic violence are common themes.

Parent advocates said those cases fall into shades of gray, ripe for a zealous defense attorney to sway a judge or jury. Lawyers could bring in experts to question CPS’ judgment or push hard for more robust services.

Michigan does little to incentivize such advocacy. It's certainly not the pay.

In Eaton County, for example, lawyers are paid $40 an hour to represent parents at the Court of Appeals, a fraction of what they can make on the divorce and custody cases they handle in private practice, and their pay is capped at $800 per case.

At the trial court, lawyers often argue in front of the very judge who hired them, and that “makes lawyers nervous about how they present their case,” said Jim Fisher, a retired Barry County judge who chairs the new Michigan Indigent Defense Commission. “Will the judge continue to appoint them if they are too aggressive?”

Seven Michigan counties have a public defender office independent of the courts. Few of them represent parents in CPS cases.

Because there are no statewide standards for these attorneys, “most places find it difficult to evaluate the adequacy of the services that are being provided,” Fisher said.

The Legislature has promised to help counties meet new standards developed by Fisher’s commission, but that work is statutorily limited to criminal cases.

The result: A 2009 report from the American Bar Association, the only statewide assessment, described parents' attorneys who rarely meet clients before their first court appearance, rarely perform research or advocacy outside of the courtroom, and are so overburdened with cases they invest little time in any of them.

Invoices from court-appointed lawyers working in Greater Lansing show they billed for little time outside of court and almost never sought expenses for independent assessments such as psychological evaluations. Judges hear only from experts paid by DHHS.

Flagg, the Mecosta County dad, was hurt in court when he failed a CPS polygraph and by damaging testimony from a CPS-paid psychologist. His court-appointed attorney, Kim Booher, never asked for independent experts. Now a judge, Booher declined to comment for this story.

Later in his trial, Flagg’s family mortgaged his grandmother’s house and hired an attorney. The first thing the new lawyer did was commission another polygraph, which Flagg passed, and get the opinion of an independent psychologist who questioned the DHHS professionals’ work.

Ultimately, the judge believed DHHS’s experts, but Flagg wonders what might have happened if he’d had those reports earlier, in front of a jury.

‘That sense of responsibility’

Attorneys, for their part, said they’re often stymied by the parents themselves: Letters to clients are returned to sender, phone calls go unanswered, and mom or dad are absent from court.

“That’s what really bothers me, is when you have a child that has already been taken away from you, and you don’t have that sense of responsibility,” said William Metros, a Bath lawyer who’s represented both parents and kids for 20 years.

Judges said they can — and have — removed attorneys for failing to adequately represent their clients. Ingham County Judge George Economy said he appoints only the most experienced lawyers on CPS cases, so “there aren’t any newbies coming in.”

Neil O’Brien, the prosecutor in charge of CPS cases in Eaton County, said parents' trials have more checks and balances than criminal cases because everyone argues for the best outcomes for kids. The defense, prosecution, kids' attorneys and the judge are all pushing for the same goal, so "nothing gets lost in the process."

Yet he does more homework than his opposing counsel. O’Brien sometimes makes attorneys available at the DHHS office just to answer general questions from caseworkers, for example, while records show defense attorneys rarely speak to clients one-on-one outside of court, and then typically on the phone.

Judges granted terminations on nearly two-thirds of the parent-child relationships the agency wanted severed in 2014. Only six of the 109 appeals from Ingham, Eaton and

Clinton counties between 2010 and 2014 were sent back to the circuit court for reconsideration. None of those parents had their parental rights restored by the appellate court.

“I’ve just seen so many cases where (termination) could have been avoided if they had bothered to try,” said Speaker, the appellate attorney.

‘This is an answer’

Tiffany Stachiw is trying.

Like the DCFA in Detroit, Stachiw is providing Genesee County parents targeted social work beyond what the state can or will offer. She's part of a pilot program that has essentially doubled the reunification rate there.

Stachiw recalled a young mother who was skipping supervised visits with her child, hurting her case in court. The mom told Stachiw she didn’t know how to properly make a bottle or put a diaper on her baby, and she knew DHHS was logging every failure.

Stachiw went to the mother’s home and taught her how to do it.

The mom started going to her visits.

“The way the system is set up, it makes it hard for the (state) worker or the parent to succeed,” said Judge Kay Behm, the Genesee County judge overseeing the pilot program. “This is an answer to the systemic problem.”

Behm said Stachiw “frees up my attorneys to be attorneys.” At DCFA, staff attorneys help parents with “collateral legal issues” that make judges hesitant to place kids with their relatives. They may file personal protection orders against abusive spouses, take legal action against slumlords, or deal with outstanding arrest warrants.

The programs in Detroit and Flint work. And they’re cheap.

Nearly seven in 10 of Stachiw’s cases ended in reunification, for example, compared to 32% of cases without her help. Her cases closed faster. And, based on the number of kids in foster care and what the Legislature set aside just for foster care payments, keeping 18 kids with their parents could cover Stachiw's $260,000 five-year budget.

Michigan isn’t investing in this kind of work. The Detroit operation is funded through a mix of private foundation dollars and a unique match from Wayne County Child Care Fund dollars. The Flint pilot was funded in its first year by the federally backed Court Improvement Program and in subsequent years by the Casey Family Foundation.

Behm's grant is about to expire. She wants to ask her county board for the money to keep Stachiw on. The board is wrapped up in the Flint water crisis, so the judge is pessimistic.

Which is sad, the judge said, because of the difference Stachiw can make for families.

McGaughy, the Detroit barber, got to keep his kids. His daughter, 12, is “a cool little character,” he said. His 11-year-old son is struggling in school, but coming along. They even visit their mother.

Because of DCFA's help, he’ll get to raise them how he was brought up: in the church, food on the table every night, knowing the importance of family.

“I ain’t gonna let them just grow up,” McGaughy said. “I’m gonna teach them everything I know.”

Related reading:

- Full coverage: Ricky Holland case, 10 years later

- UAW: Michigan DHHS wants to outsource CPS work

- Foster care will not be privatized, officials say

- Michigan meets child welfare goals

For more information

Michigan Department of Health & Human Services: michigan.gov/mdhhs

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Administration for Children & Families: acf.hhs.gov

Suspect abuse or neglect? Call 855-444-3911

Complaint about an attorney? Contact the Michigan Attorney Grievance Commission at agcmi.org or 313-961-6585

Complaint about Children’s Protective Services? Contact the Michigan Children’s Ombudsman at michigan.gov/oco

Care to comment?

You can send us a letter to the editor. Find the form here.

How this story came together

This story started with a brief report in July 2015, on the 10th anniversary of the death of Ingham County foster child Ricky Holland, that detailed the ways Michigan continues to fail foster kids. After that story published, Lansing State Journal investigative reporter Justin A. Hinkley received numerous phone calls from parents claiming the Michigan Children’s Protective Services had taken their kids away without cause. The State Journal decided to dig.

Over the following several months, Hinkley conducted dozens of hours of interviews with parents, attorneys, judges, researchers, advocates, state officials and current and former CPS workers. He reviewed hundreds of pages of documents, including court records, invoices from court-appointed attorneys, research papers, and miscellaneous reports on CPS and court activity. He traveled to Detroit, Mecosta County and various places in Greater Lansing for interviews and to review records. State Journal criminal justice reporter Matt Mencarini assisted in finding and reviewing records.

Contact Justin A. Hinkley at (517) 377-1195 or jhinkley@lsj.com. Follow him on Twitter @JustinHinkley. Sign up for his email newsletter, SoM Weekly, at on.lsj.com/somsignup.